This film leaves me the strange aftertaste.

Its heavy-handed acting, brooding plot elements, very ideological characterization, and misery of massive edit, all contributed to the unfortunate “almost-there-but-not-quite” quality of this film. I guess this film is filled with everything Kurosawa detractors deplore about his works. Too ideological to be visual arts, “humanity” spelled out every places, Japanese don’t act like that, etc. Especially considering the fact that Setsuko Hara and Chieko Higashiyama would make such impressive performances in “Tokyo Story” two years later, many seem to feel great Ozu actors were wasted in this work.

However, my “strange aftertaste” may have something to do with something else also. It may have to do with the location of this film, Hokkaido.

Hokkaido and Cold War

In 1976, a Soviet fighter jet, MiG-25, landed on Hakodate airport, located in the southern peninsula of Hokkaido. Lieutenant Victor Belenko defected to Japan, seeking asylum in U.S., riding on Soviet’s state-of-art, top secret airplane. This created shock waves to whole Western world (and, of course, Soviet Union), and the plane was studied thoroughly both by Japan and U.S. The most serious concern for Japan was the fact that a Soviet jet fighter could penetrate into the Japanese territory with ease, though Japanese Air Defence did dispatch the several jets to counteract the intrusion. I was still a little kid back then, but still realized there was an immediate danger of being invaded by the Soviets. And the first place they would land would be Hokkaido.

Since the end of WWII, Hokkaido had been one of the invisible battle fronts of the Cold War. Even now, Japanese government and Russian Government have on-and-off territorial disputes over four islands north of Hokkaido. At the time of very end of WWII, Hokkaido could have been easily “fifth” island of that dispute.

Therefore, in 1951, the year of this film production, the place was becoming the center of national defence. In the previous year, SCAP/GHQ, with Japanese government, created National Police Reserve, the precursor of Japan Self-Defence Force. The creation of militarized police in Japan was the result of emerging Cold War.

Hokkaido had been considered as a sort of colony since 19th century. Japanese Government had many relocation programs, land development plans, railway system constructions, agricultural research, natural resource development and creation of Native (Ainu) Reserves. All of those activities were done under the name of modernization, industrialization and colonization. Due to its vastness and abundant land, everything in Hokkaido is much larger and full of space compared to those in rest of Japan, From Hokkaido, the Honshu (the largest island in Japan) is “In-Land (内地)”, meaning the land that is inside of the periphery, contrasting Hokkaido being periphery. It had been a separated island with different habitat and geopolitical entity.

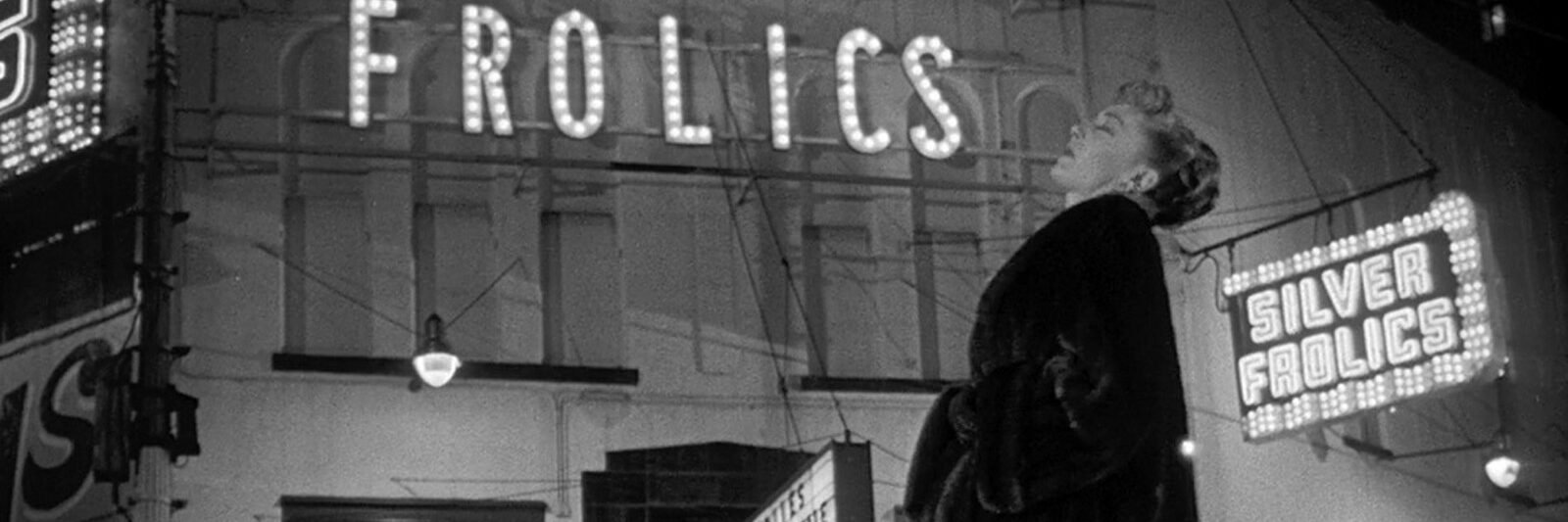

Then, refurbishing the Russian novel into tormented story in Cold War front Hokkaido is juxtaposition of multiple layers of uneasiness. Characterization and acting is so foreign that we wonder if Mifune, Hara and others were at loss during the production. Location shooting and art do not belong to typical 50’s Japan. Many say this film has a look of an European film of the era. And moreover, the story of innocence and ego is rarely treated in this direct manner during postwar years. It seems this Hokkaido was under occupation of some foreign country.

Stylization

It is obvious that Kurosawa aimed at recreating the great Russian writer’s world in snow-bound Hokkaido. The problem starts with this “recreation”. His other films were also based on Shakespeare, Gorky and other literary works, but for these works, Kurosawa stripped the story to the bare essence before adapting into Japanese scenery. Apparently, he hesitated doing so with this film. He wanted to do Dostoevsky. And it betrays the whole point of making a film.

The most apparent breakdown is Kameda/Myshkin character. Myshkin is an ideological entity in the novel, quite successfully so, since the world of literature can handle metaphysical theme through textual molding. However, the such an ideology-centric approach is not readily available in narrative films. The reason is simple; texts command the discrete, selective approach while visualization of the character in a story demands total interpretation. What happened here appears to be representation through stylization. You see that Kameda’s posture is stylized throughout the film to represent his position in the film; clutching his coat’s lapels whenever he needs to defend his perimeter. We, the viewers, tend to be confused by such representation, because we see somebody manufactured on a story board.

But we do have Kabuki, visual/performance arts stylized to the point of perfection. Why is this not working?

Problem with Innocence

I believe that the what Kameda/Myshkin represents, the notion of “innocence”, is hard to sell in this context. No matter how it is explained, the character of Kameda is far from the spectrum of postwar Japan. Indeed, it might have been quite a fascinating experiment; an innocent spirit at the focal point of Cold War front immediately after the World War. But an spirit in Dostevsky’s story is not directly transferable to the world of 1950 Japan. You need to disassemble/reassemble the character to fit to the world of such a abnormal intensity.

In Minoru Shibuya’s “Honjitsu Kyuusin (本日休診, 1952)”, an innocent soul aggravated by war experience is depicted to much more satisfying results. The PTSD soldier do cause a havoc in the neighborhood, but it is about how neighbors live with his scar, not with him. In the end, we see the neighbors share the scar, which leads to acceptance of the past tragedy. That is so rewarding since we have less concerned about innocence itself, but about the loss of it, specifically our loss of it.

St.Petersburg in the original novel was the center of culture in Russia at the time, with decadent upper class and polarized working class. Hokkaido in 1950s was the frontier of not only Japan itself, but the Western world. The place might have been under multiple layers of contradiction, but it was definitely not the place of climax phase of human greed as in the original novel. Then, only the imagery St.Petersburg being transferred to Hokkaido remains, creating the illusion that the place was foreign to “In-Land” Japanese.

The strange aftertaste is that of vodka mixed with Japanese seafood platter. And it always gives me a splitting headache in the next morning.

The Idiot (白痴)

1951, Shochiku

Prod. Takashi Koide

Dir. Akira Kurosawa

Writer Eijiro Hisasaka, Akira Kurosawa

Cinematography Toshio Ikukata

Music Fumio Hayasaka

Starring Masayuki Mori, Toshiro Mifune, Setsuko Hara, Takashi Shimura

Copyrighted materials, if any, on this web page are included as “fair use”. These are used for the purpose of research, review or critical analysis, and will be removed at the request of copyright owner(s).